In this conversation with architect, researcher, and professor Manuela Valtchanova, we explore how her multidisciplinary background in architecture, ephemeral design, and art theory informs a radically open, process-based approach to public space and ecological engagement. From her academic influences and personal experiences growing up in post-dictatorship Bulgaria to her participatory, site-specific projects like Anarchaeology of a Field, Manuela reflects on the power of artistic action as a catalyst for social, political, and environmental transformation. She discusses the critical role of doubt, contradiction, and creative obsession in shaping her practice, while offering a compelling vision for sustainability grounded in informal gestures, non-human agency, and collaborative reimaginings of space. The conversation unfolds as a deep meditation on how to activate resistance, imagination, and long-term emotional investment through artistic strategies that are as poetic as they are politically engaged.

Manuela Valtchanova. Architect, researcher and professor. PhD in Aesthetics and Theory of Arts. Her area of work is based on the critical transaction between politics, space and affect, with a special interest in the possibilities of direct action. In her professional career, she carries out projects that address heterogeneous architectural and artistic formats between temporary interventions in public space and socio-spatial practices of collaboration and mapping. She has been visiting professor and guest lecturer at universities worldwide and she has published both specialized articles and book chapters, mainly addressing counterdisciplinary strategies through direct action, cartographies, embodied exploration and performative criticality.

Manuela Valtchanova. Architect, researcher and professor. PhD in Aesthetics and Theory of Arts. Her area of work is based on the critical transaction between politics, space and affect, with a special interest in the possibilities of direct action. In her professional career, she carries out projects that address heterogeneous architectural and artistic formats between temporary interventions in public space and socio-spatial practices of collaboration and mapping. She has been visiting professor and guest lecturer at universities worldwide and she has published both specialized articles and book chapters, mainly addressing counterdisciplinary strategies through direct action, cartographies, embodied exploration and performative criticality.

At E-ART, she acts as a mentor and curator for the Barcelona-based E‑ART ART LABS Residency focused on upcycling found objects.

Interview by Yelyzaveta Adamchuk

Tell us more about yourself and your practice. Your background spans architecture, theory of arts, and design research. How has this multidisciplinary training shaped the way you approach public space, artistic intervention, and social engagement?

I studied Architecture, followed by a master’s degree in Ephemeral Architecture, and then pursued a PhD in the Theory of Arts. The reason for this shift was an intellectual admiration I had for a curator named Martí Perán. Although I didn’t personally know him initially, I had read many of his books and visited several of his exhibitions. To this day, I remain deeply inspired and overwhelmed by the narratives he creates.

When I received my scholarship for doctoral studies, I had the freedom to choose any area. The conventional route would have been to pursue a PhD in architecture, but instead, I reached out directly to Martí Perán. I sent him an email asking if we could discuss the possibility of him mentoring my PhD. Surprisingly, he agreed. The entire doctoral process was extraordinary. For approximately five years, every conversation with Martí provided me with immense inspiration, new ideas, and urgency to explore additional references. During the first two years of my PhD, I attended numerous courses on art philosophy, from undergraduate to master’s levels, to fully grasp what my research entailed. This intense period was deeply challenging, frustrating, yet profoundly enriching. I relate this experience to the “post-balkan” syndrome”, where trauma and suffering become catalysts for creativity and deeper insights.

This period represented a collapse of my comfort zone and preconceived ideas, forcing me to push beyond my limits and expand my interests.

You often work at the intersection of art, activism, and urbanism. What motivates you to operate across these fields, rather than within traditional architectural or academic frameworks?

I recall participating once in a forum called Forum Indigestió, where each participant had five minutes to speak freely. Unexpectedly, I began discussing the deep contradictions and dichotomies shaped by my upbringing and experiences, particularly growing up in post-dictatorship Bulgaria. I described vivid memories like queuing for bread, desperately wishing for the first Barbie doll, and the excitement of visiting the first McDonald’s, symbolic of a new Western era. Ironically, I’ve been vegetarian for twenty years and haven’t eaten McDonald’s since that initial three-hour wait.

Later, after moving abroad, these contradictions deepened. In Barcelona, at a party, people sang enthusiastically about the return of the USSR — a song “Que vuelva la URSS”. Initially, it horrified me, triggering memories of my family’s harsh experiences under Soviet-influenced dictatorship. Yet, years later, I found myself participating in demonstrations supporting Pablo Hassel’s freedom. These contradictions exemplify the ongoing tension between my lived experiences and my current beliefs and ideals.

My academic and professional journey mirrors this internal struggle. Studying architecture, I began questioning its ideological implications—how architecture in Bulgaria served as a political and cultural tool, promoting an idealized Western lifestyle. After studies in different places around Europe, I arrived in Barcelona, where my expectations collided with local creative realities

This hyperactive period led me to explore intersections between art, architecture, and social interventions. Though hesitant to label this as activism, I became deeply interested in the phenomenology of activist actions—how direct interventions in urban spaces activate extraordinary social, cultural, ethical, and political dynamics. My PhD research revolved around these phenomena, experimenting practically and philosophically with collective actions and community engagement.

All these internal contradictions, ideological shifts, and constant movement between disciplines define my ongoing journey—a continuous effort to understand, develop, and implement meaningful ideas amidst perpetual internal and external struggles. Now, having completed my PhD in 2022—three years ago—I reflect positively on these contradictions and challenges, recognizing them as among the most meaningful and constructive experiences of my life.

One exhibition by Martí Perán that particularly influenced me explored entropic structures beyond traditional architecture, questioning modernist patterns, order, and discipline. He argued that modernist architecture imposed a pre-established political and social order through hygienization and hierarchical organization. As a counterpoint, he highlighted informal, entropic constructions and installations that challenge these norms. This concept became central to my PhD hypothesis.

Martí’s essay, “(Des)Encuentros entre Arte y Arquitectura”, further shaped my interest in artistic happenings and ephemeral installations. Another important essay, “Ensayo sobre la Fatiga, Derecho a Indisposición,” discussed the right to inactivity and fatigue as forms of activism, emphasizing the value of stepping outside society’s productivity demands. This resonated deeply with my exploration of hyperactivity in the neoliberal context, where constant productivity often dominates our lives.

His recent research on the figure of the “idiot” across literature, philosophy, cinema, and art also intrigued me, exploring the creative potential of those marginalized or considered unproductive.

Sustainability is a term with many layers. Beyond policy or technical definitions, how do you relate to it as a practitioner: ethically, artistically, or methodologically?

There’s extensive development regarding sustainable architecture, sustainable practices, sustainable creative processes, sustainable societies and cities, and a sustainable planetary vision, among other things. Ultimately, all my research during my PhD and afterward revolves around a core hypothesis. This hypothesis relates to an ideological perspective on how our society should function. However, my primary interest lies in exploring and experimenting with how everyday attitudes, informal actions, and small gestures—gestures of resistance, desire, imagination—that transcend formal disciplinary boundaries, can become contagious and viral. These informal, everyday actions can foster a critical state of mind that is significantly more impactful than isolated interventions initiated from privileged positions of power.

As creative agents or professionals within creative industries, we inherently occupy positions of privilege. One compelling hypothesis for me is how this privilege can be temporarily suspended or disrupted, reframing it as a tool to activate other agents operating from different contexts and spaces. These other agents hold the potential power to transform our lived environments and territories. Therefore, sustainability, to me, fundamentally revolves around an everyday vision: how we compromise, how we relate to our surroundings, context, and personal vision of the place we inhabit. Recognizing this place as part of a complex network—not solely human but involving numerous non-human realities not subordinate to human existence—is central.

This complex vision intentionally disrupts our anthropocentric actions, enabling us to perceive ourselves as part of a broader network of interactions. This notion has consistently been central to my work and represents a fundamental hypothesis within sustainability or related philosophies. The current dominant discourse, often propagated by right-wing narratives, frames sustainability as an area reserved only for those who can afford to be sustainable—treating ecology merely as an engine to propel privileged economies driven by local interests. Such a perspective requires disruption. Survival and progress must be understood as interconnected, complex networks in which everyone can contribute from their own sphere of influence.

Moreover, it is essential to overcome the widespread sense of general anesthesia caused by the constant bombardment of distressing images—migrant deaths, wars, genocides—and an omnipresent feeling of guilt for the planet’s imminent collapse. This persistent unease, anxiety, and exhaustion undermine our sense of agency, leaving us feeling helpless and powerless. Therefore, creating small moments of desire, illusion, and imagination becomes critical. Transforming moments of exhaustion and anxiety into opportunities for creativity and empowerment is particularly fascinating to me. Some of my experimental projects have partially realized this concept, offering promising preliminary insights. Further exploring and developing these ideas represents an important direction for my future research.

Could you tell us more about the projects where you influenced this kind of tension or contradiction, as in your project Anarchaeology of a Field — especially in terms of its connection to the EART project overall?

Yes, there are definitely some connections—especially in terms of how to activate different forms of agency around a common issue. Not just the agency of us as artists or designers, but also non-professional forms of agency.

In this case, the project was a proposal I submitted for an open call focused on art and the city. The call didn’t specify a site or project type, but in past editions, the selected works had always ended up as exhibitions in Casa de la Cultura in Sant Cugat.

When I saw that, my intuition was: if we’re going to talk about art and the city, then let’s move artistic production out of the exhibition space entirely—out of the museum—and redirect the attention, resources, and infrastructure toward a site that’s both neglected and politically charged.

So I began working with this abandoned golf course—a place that’s long been at the center of various social and political tensions. Back in the 1980s, there was a strong social movement against the course’s construction. Residents of the district mobilized for two main reasons: one, to protect the ecological corridor that connects Collserola with Barcelona, and two, as an act of resistance against class-based urban expansion. The golf course itself became a symbol of exclusive, upper-class development.

Sant Cugat, where the course is located, is quite interesting in terms of class dynamics and urbanism. Even the way social housing and public spaces are designed there often ties back to concepts like “social hygiene.”

As I kept researching, I discovered the course was shut down in 2018. For several years till today it has remained closed off—surrounded by a massive fence. Interestingly, despite multiple urban planning attempts to repurpose the area—first into luxury housing, later into social housing—nothing was done. During that time, more than 50 local associations advocated to preserve the space as a public green corridor.

And yet, it just sat there. Untouched. A strange moment of stillness right in the middle of a city in flux.

And something beautiful happened: biodiversity flourished. A report was even made listing all the new animal and plant species that had returned since 2018. It became a refuge—visited mostly by people wanting to disconnect from their daily routines.

That’s when I thought: what if we re-centered artistic production around this contested site? One of my first ideas was: what would happen if I took the entire project budget and, instead of producing an artwork, gave it to a shepherd and their animals?

This would allow the project to support an underrepresented sector—agropastoralism—while also repositioning it as a central agent in the artistic act.

Shepherds have recently gained attention in places like Collserola for their role in fire prevention—grazing to reduce dry vegetation. But they still lack visibility, support, or infrastructure. It’s a paradox: their work is crucial but legally and socially invisible. So I decided the shepherd and the animals would become the main protagonists.

The second layer of the project was about the idea of more-than-human patterns of inhabiting space. On one hand, of course, you have animal behavior. But I also saw “more-than-human” as about non-productive, non-goal-oriented behavior—alternative ways of engaging with space.

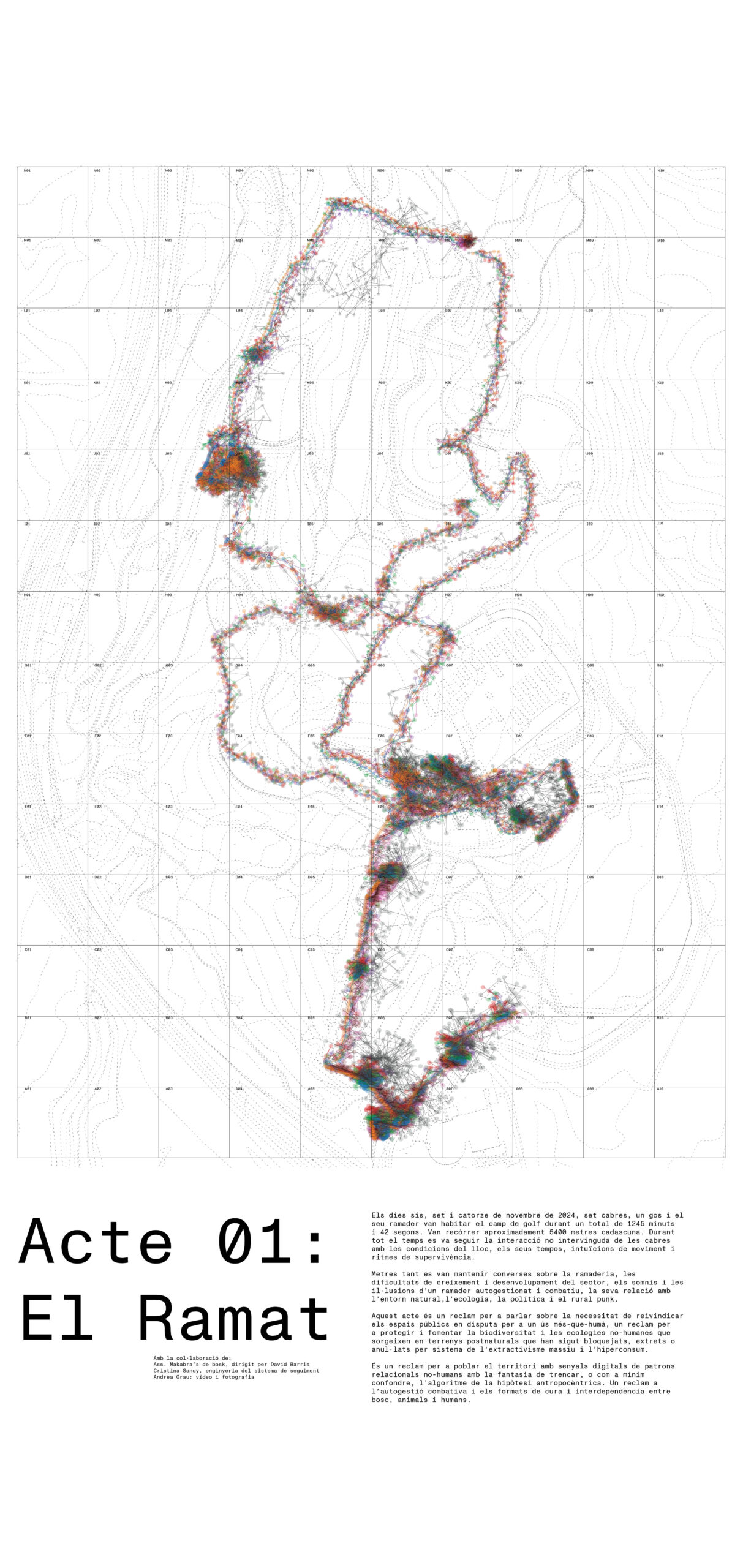

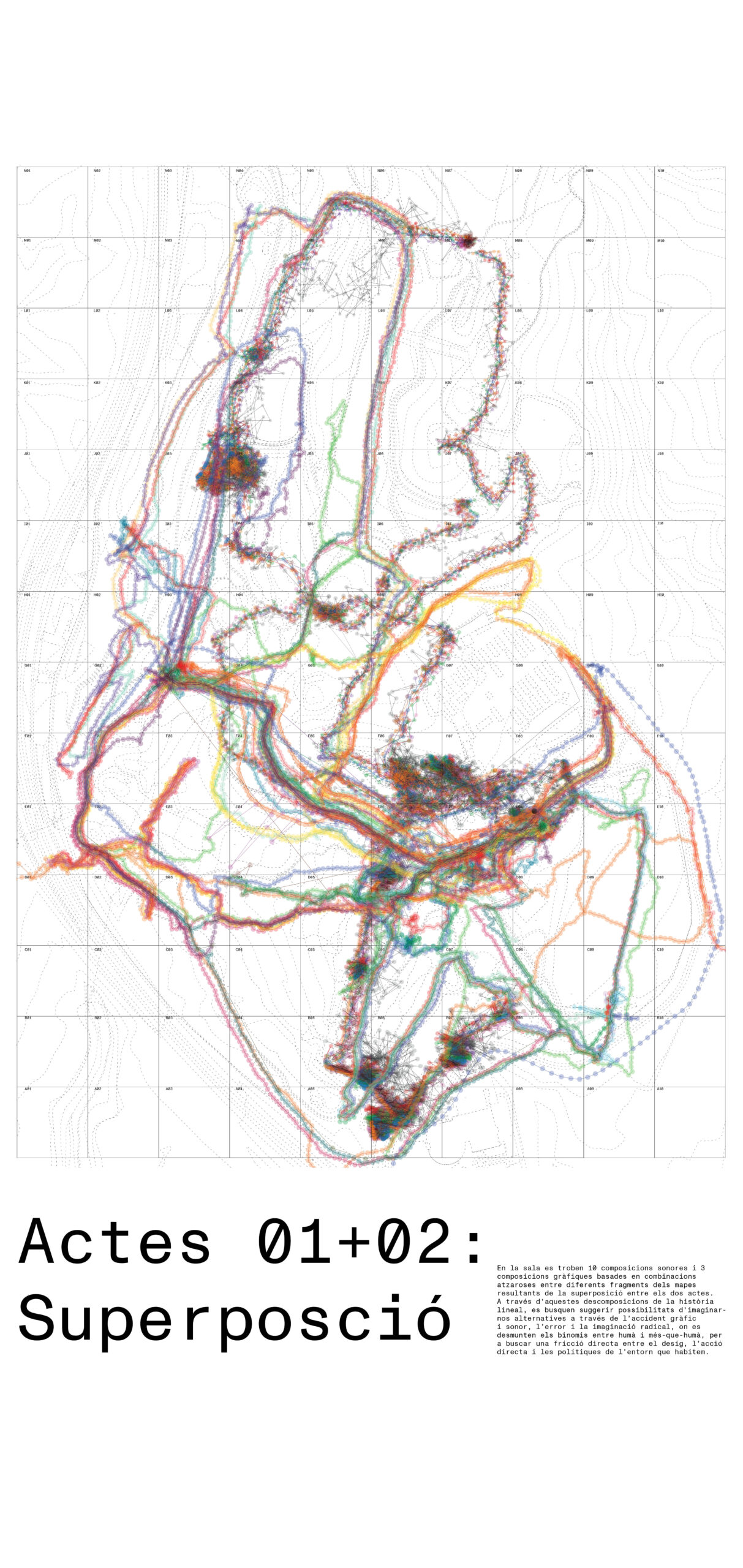

Act 1 The Herd: we spent three days in the golf course with one shepherd and seven goats. Each goat was fitted with a GPS tracker, and their movements were translated into digital data.

This had two purposes: first, to disrupt the usual digital representation of space. Platforms like Google use human mobility data to define place. I wanted to inject non-human, instinct-driven behavior into those algorithms. And second, I transformed their GPS paths into sound compositions.

It was a way of creating another layer of interpretation—one that’s not visual or functional, but intuitive, accidental, chaotic. The movements of the goats became sound, and those sounds then became the basis for a kind of rave party.

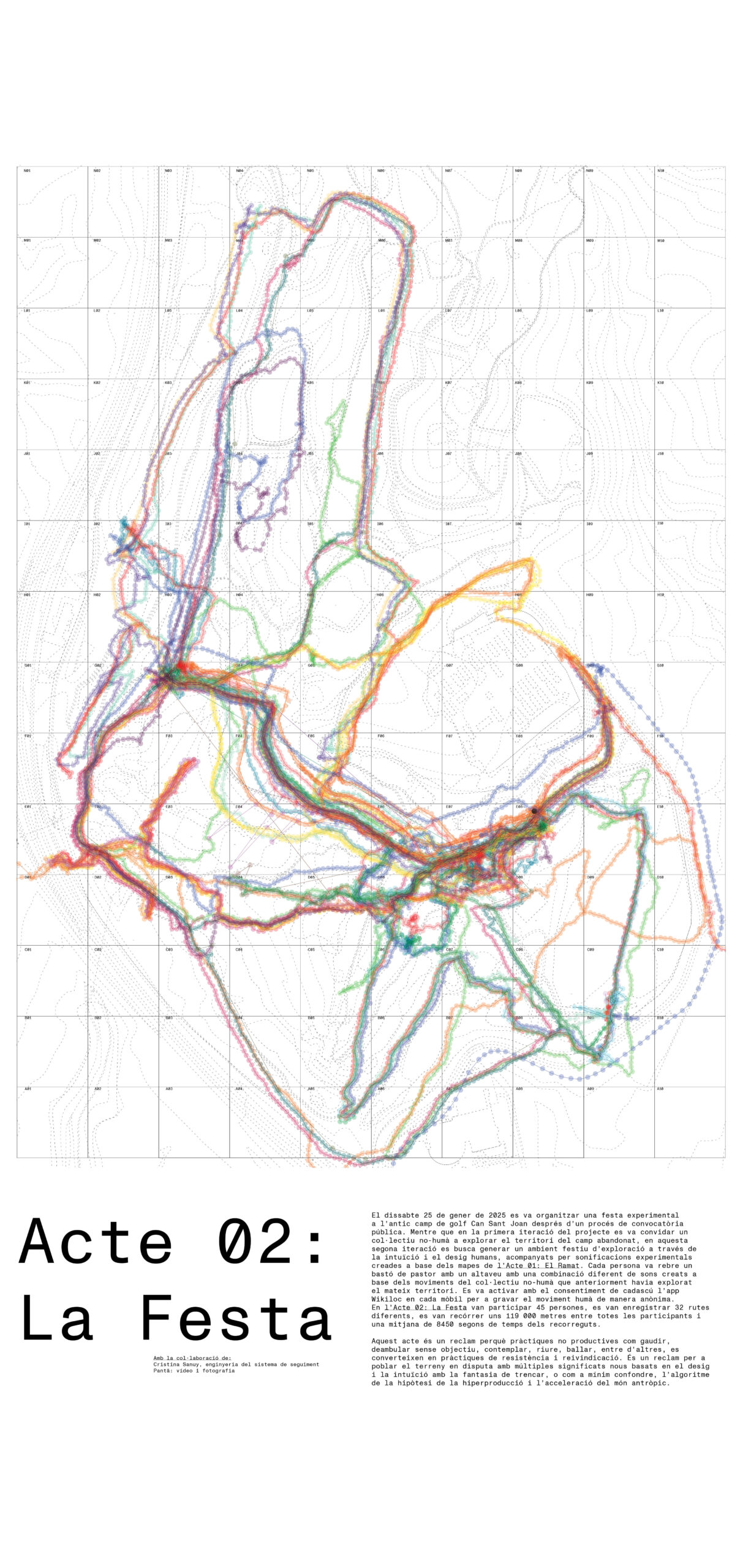

Act 2 The Party was a participatory event. We made an open call, and 48 people showed up. We entered the site through the closed fences. I split them into 10 groups, and each group received one sound composition and a shepherd’s staff embedded with a speaker.

They were free to roam, dance, get lost—whatever they wanted. There was no structure, just pleasure-based wandering. I tracked their movements anonymously again, not as data for utility, but as a way to hack the logic of surveillance and reclaim the right to move without purpose.

It was totally chaotic, but for three hours, all kinds of social boundaries dissolved. No one cared who you were or where you came from. And again, all of their movements were tracked and converted into maps—now layered with the earlier goat movements.

Then came the exhibition. I had to show something, of course—so I presented the maps of the goat and human movements, plus a video documenting the platform Reconvertim el Camp de Golf and its activism.

But the real point of the exhibition was not what was inside the gallery—it was the invitation to go outside. I wanted every visitor to leave, go to the site themselves, and decide: do you want to join this fight? The exhibition was a call to break through apathy.

We need to position ourselves—either for or against—but to remain passive is no longer acceptable. That’s the real aim: to cultivate a collective critical attitude, to ask, what kind of city do we want?

The whole project was about engaging with the goats, the shepherd, the people, the sounds—and understanding all these behaviors as forms of questioning: how goats survive, how people have fun, how shepherds navigate an invisible profession. The site became a lab—a prototype for new ways of being in contested urban environments.

And while working on this project—or in your other projects—have you found yourself using repurposed materials or found objects? I mean, in this project, you almost didn’t create any new production. You worked with the community, the shepherd already existed, the landscape was already there—nothing had to be built from scratch like in galleries or institutions.

Yes, in this project, the idea of the “found object” was a key element. For me, in this project, the found object was actually the goats’ behavioral patterns. Their movements and instincts became the raw material. That was the starting point, and everything else in the process was built around and on top of that.

In terms of climate change and ecological commitment, I wasn’t trying to intervene in a direct or didactic way. Instead, the goal was to highlight all the invisible ecologies—forms of life and transformation that are happening there, unnoticed. We usually don’t think of these when we imagine a site or a city. So the project was more about posing a question: What is happening here now? What has emerged simply because the space was abandoned?

But in another project I did a few years ago, in Sant Boi de Llobregat—specifically in Plaça de la Generalitat—it was a different approach. That square was a highly stigmatized public space. It used to be one of the central plazas of the district, but it had become marginalized. People avoided it because of the surrounding communities and what were considered “unacceptable” behaviors.

So we started working there, and one of the main questions was: how do you intervene in the imaginary of a place without making permanent changes? How do you avoid imposing a fixed meaning, and instead create conditions for new interactions—between the space and the community?

Our proposal was to engage all the schools and associations in the district. In the end, we activated around 1,000 children. Each child was asked to bring a sock and to personalize it—draw on it, write a wish, put a message inside—whatever they wanted.

Then we organized a collective activation day. We installed a lighting network—one kilometer long with 1,000 light bulbs—and each child, with their family, came to hang their sock on the network. The entire square was transformed. It was filled with these personal objects, memories, and wishes.

What made it beautiful was that the children brought their own creations. Our role was just to provide the infrastructure. And after the project officially ended, that infrastructure—the network of bulbs—was stored in the local cultural center, the Casal. It actually became a new tradition. Since 2020, every year they take it out and organize a new action with people from the district.

That kind of lasting engagement—where you disappear, but the relationships and interactions continue—is very powerful. It creates a kind of long-term emotional and social investment.

So in that case, the objects weren’t “found” in the traditional sense. They were brought in by the people, by the kids. But each one was chosen, personalized, and activated by them.

It’s a way of building on top of your own environment—your own material world—to participate in a collective, imaginative experience. That’s also a kind of strategy for working with found materials. Because we all have objects. We find them all the time. But it becomes really interesting when you start decontextualizing them—putting them into a new frame—and letting them gain critical potential.

You’re mentoring artists in the E-ART ART LABS residency, which emphasizes found materials and sustainability. In your view, why are initiatives like this important – not only for artists, but also for the broader cultural and environmental conversation?

As I mentioned earlier, I think it’s really important to create cracks in our everyday inertia. We all live in these hyperactive states where we’re just coping with daily needs, and there’s very little space left for critical reflection—about what we do, where we participate, or what kind of impact we actually have on our surroundings.

It’s essential to develop new creative practices that don’t just aim to “raise awareness” in a way that adds to eco-anxiety. We need practices that go beyond that anxiety—ones that spark fascination, imagination, illusion. Moments of being overwhelmed, not by fear, but by wonder. When you see something and it moves you—not because it’s shocking, but because it’s extraordinary.

That’s why I believe artistic practice has a special role to play. It can create these extraordinary conditions that lead to fascination. And that fascination can become a kind of impulse for future action—not only for the artist, but for communities and society as a whole.

So, residencies like this—where we all come together to question ideas of ecology, nature, sustainability, and our own agency as artists, cultural workers, or simply human beings—are important. Not because they should end with a fixed outcome, but because they can generate what can be called a viral ecology of impulses: ideas and desires that ripple outward. That’s why it’s important to keep talking, keep making, keep producing things that pose questions instead of answers.

As a mentor, how do you encourage artists to engage more critically and meaningfully with environmental concerns in their work?

For me, mentoring doesn’t come from a place of authority. I don’t have a fixed idea of what should be done. It’s more an intuition shaped by my experience.

The goal is to create an open space for questioning—where artists can deconstruct their own practice in order to rebuild it again, but with new layers, more complexity, and deeper awareness. And often those new layers come from collective insights, not just individual reflection.

It’s also an opportunity to rethink artistic production itself—not just as a product, but as a process. A process where many different agents—human and non-human—are entangled.

That’s one of the most beautiful aspects of this residency: it’s open-ended, process-based. Ten artists are constantly exchanging, interacting, and co-building. Ideally, when the exhibition happens in September, it won’t just showcase objects—it will perform as a practice of fascination. Visitors might experience a moment of excitement or wonder, and that moment might become the seed for future action in their own lives.

And finally, I think you touched on this earlier, but—are there any specific materials, themes, or questions that you’re especially drawn to right now?

Right now, I’m quite obsessed with something I haven’t fully figured out yet, but it excites me a lot: I’m interested in the ecological and emotional layers of geological traumas. Especially extractive sites—like abandoned mines.

I’m drawn to these open-pit mines that were once heavily exploited and then just… left. There’s something really powerful there—these places hold trauma on many scales. From the microscopic, biological level to the planetary, satellite view.

So what I want to do is research these geotraumas at different scales—using geological analysis, microscopy, satellite imagery. Not just by myself, but in collaboration with scientists, researchers. I want to explore how these sites operate as multi-scalar systems. That’s my current obsession.

Several of your projects work with existing conditions, such as neglected urban sites, non-human presence, or abandoned infrastructures. Would you describe this approach as an ecological strategy? What values guide it?

Yes, definitely. I have this deep fascination with abandonment and decay. Because behind decay, there’s always a story—something that happened to bring a place to that state.

And those stories are important. Decay isn’t just an end—it’s a condition of transformation. Abandoned sites become places where new ecologies can emerge and grow.

So for me, studying abandonment—whether it’s places, materials, or even forgotten communities—is a way to understand not just what was, but what could be. It’s a space of opportunity.

And as an architect, do you lean more toward leaving these places as they are? Like in the case of the golf course—do you prefer to preserve the abandonment, or are you open to redevelopment, like building residential areas?

Look, obviously we can’t stop all urban development. Cities will keep expanding. But the truth is—we’ve already built so much. We’ve produced so much on this planet. It’s more than enough.

There are studies showing that just with the clothes and fabrics we’ve already produced, we could stop all textile production for the next 50 years—and still have enough.

So I think the key now is to stop creating more, and instead ask: what can we do with what already exists? What new futures can we imagine for what’s already here?

Personally, I have a real issue with the idea of permanence. Building something permanent means you’re asserting control—control over how a space looks, how it feels, what can happen there.

So for me, it’s important to preserve the temporality, the vulnerability of spaces. To leave room for change, for multiplicity, for reinvention. That’s where real ecological thinking comes in—not just in preserving nature, but in preserving the right to imagine differently.

What advice would you offer to emerging artists, architects, or designers who are trying to connect ecological awareness to their practice?

Doubt everything. Really—don’t be afraid of your own doubts, your traumas, your moments of crisis. These aren’t obstacles—they’re opportunities. When something in you collapses, it creates space for other ways of thinking, other formats of being—both for yourself and for your work.

And yes, it can be painful. But we’re here to be brave with that pain. To let it guide us, to transform it into creative energy. That’s part of the journey.

Don’t be afraid to become obsessed. You need that energy, that mania, to push your practice forward. The “middle ground,” where everything is healthy and balanced, is fine—but obsession can be a great catalyst.